Math Topics

Learning Support

Professional

![]()

Math Methodology is a three part series on instruction,

assessment, and curriculum. Sections contains relevant essays and

resources:

Math Methodology is a three part series on instruction,

assessment, and curriculum. Sections contains relevant essays and

resources:

Part 1: Math Methodology: Instruction

Part 2: Math Methodology: Assessment essay and resources

Part 3: Curriculum: Content and Mapping and resources

![]()

Although learning for understanding is unique to an individual, teachers

can enhance the process of learning with their own knowledge of how people

learn. The National Research Council (2005) stated three fundamental and

well-established principles of learning, which all teachers should

understand and address in their teaching:

Although learning for understanding is unique to an individual, teachers

can enhance the process of learning with their own knowledge of how people

learn. The National Research Council (2005) stated three fundamental and

well-established principles of learning, which all teachers should

understand and address in their teaching:

Research has shown that "metacognitive and cognitive abilities are not

naturally endowed" (Wilson & Conyers, 2016, p. 8). Educators should not

assume that students will naturally acquire metacognitive (i.e., thinking about

one's thinking) strategies for learning, as they delve into their courses. They must be explicitly taught

and learners will need intensive practice for when, how, where, and why to use

them (pp. 7-8). Wilson and Conyers provide such strategies in

Teaching

Students to Drive Their Brains: Metacognitive Strategies, Activities, and Lesson Ideas.

Research has shown that "metacognitive and cognitive abilities are not

naturally endowed" (Wilson & Conyers, 2016, p. 8). Educators should not

assume that students will naturally acquire metacognitive (i.e., thinking about

one's thinking) strategies for learning, as they delve into their courses. They must be explicitly taught

and learners will need intensive practice for when, how, where, and why to use

them (pp. 7-8). Wilson and Conyers provide such strategies in

Teaching

Students to Drive Their Brains: Metacognitive Strategies, Activities, and Lesson Ideas.

In their introduction to mathematical understanding, Karen Fuson, Mindy Kalchman, and John Bransford (National Research Council, 2005, pp. 217-256) noted some of the preconceptions that students might have about mathematics: Mathematics is about learning to compute; Mathematics is about "following rules" to guarantee correct answers; and, Some people have the ability to "do math" and others don't. Teachers must engage those, as they can be counterproductive to learning and contribute to students' lack of desire to study mathematics.

As mathematics educators, we want our learners ultimately to be mathematically literate and proficient in mathematics. To achieve this, educators will need to focus on deeper learning and learning for understanding. By deeper learning, we mean "the process through which a person becomes capable of taking what was learned in one situation and applying it to new situations – in other words, learning for “transfer.” Through deeper learning, students develop expertise in a particular discipline or subject area" (National Research Council, 2012, p. 1). It involves six "competencies students must master in order to develop a keen understanding of academic content and apply their knowledge to problems in the classroom and on the job. [Students must] master core academic content, think critically and solve complex problems, communicate effectively, work collaboratively, learn how to learn, [and] develop academic mindsets" (Hewlett Foundation, 2013).

Volker Ulm (2011) noted that mathematical literacy involves several competencies:

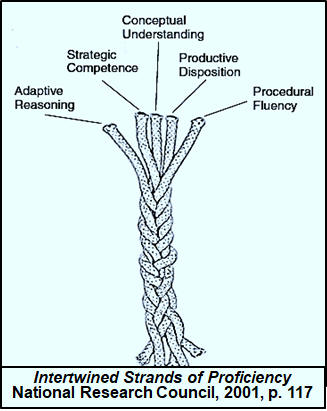

Developing proficiency, as the National

Research Council (2001) pointed out, embodies "expertise, competence, knowledge,

and facility in mathematics" and the term mathematical proficiency

entails what is "necessary for anyone to learn mathematics successfully" (p. 116).

It has five interwoven and interdependent strands:

Developing proficiency, as the National

Research Council (2001) pointed out, embodies "expertise, competence, knowledge,

and facility in mathematics" and the term mathematical proficiency

entails what is "necessary for anyone to learn mathematics successfully" (p. 116).

It has five interwoven and interdependent strands:

conceptual understanding—comprehension of mathematical concepts, operations, and relations [Note: for more on conceptual understanding, read Conceptual Understanding in Mathematics by Grant Wiggins (2014).]

procedural fluency—skill in carrying out procedures flexibly, accurately, efficiently, and appropriately

strategic competence—ability to formulate, represent, and solve mathematical problems

adaptive reasoning—capacity for logical thought, reflection, explanation, and justification

productive disposition—habitual inclination to see mathematics as sensible, useful, and worthwhile, coupled with a belief in diligence and one’s own efficacy. (National Research Council, 2001, p. 116)

Becoming mathematically literate and proficient are ongoing processes. Writing in IAE-pedia, David Morsund and Dick Ricketts (2010) noted that becoming proficient is a matter of developing math maturity, which certainly varies among students and which involves how well they learn and understand the math, how well they can apply their knowledge and skills in a variety of math-related problem-solving situations, and in their long term retention.

While teachers have a role to play in helping students to develop understanding, students also have a role to play in the process, which cannot be overlooked. They must have intrinsic motivation, as in Eric Booth's (2013) words: "Learning can be transformed into understanding only with intrinsic motivation. Learners must make an internal shift; they must choose to invest themselves to truly learn and understand" (p. 23). This kind of motivation involves fulfilling their need for creative engagement, which is where the teacher's role in the design of instruction and corresponding assessments comes into play.

Understanding "typically entails being able to explain processes and relationships, apply conceptual knowledge to new situations, and interpret ideas in intended ways" (Zwiers, O'Hara, & Pritchard, 2014, p. 210). In mathematics, understanding goes beyond just getting the right answer to a problem. Students develop many misconceptions over time, which must be addressed in instruction. There are multiple examples to illustrate the problem.

Deborah Schifter and Susan Jo Russell (2014/2015) noted elementary students

might incorrectly subtract if regrouping is needed as in writing 46 - 18 = 32

because 4 - 1 = 3 and 8 - 6 = 2.

They might not understand that, unlike in addition,

subtraction is not commutative. Or, they might incorrectly multiply 16 x 18 as (10 x 10) + (6 x 8)

because they learned in addition you can add the tens, add the ones, and add the result

as in 16 + 18 --so why not in multiplication? Eventually, they might misinterpret the distributive

property and write 2(3 x 5) as (2 x 3) x (2 x 5). The misconception

might transfer into algebra. For example, they might write 2(ab) = (2a) (2b). Schifter

and Russell illustrated the value of students modeling problems with such examples and then describing their

observations to help overcome misconceptions. They stated:

Deborah Schifter and Susan Jo Russell (2014/2015) noted elementary students

might incorrectly subtract if regrouping is needed as in writing 46 - 18 = 32

because 4 - 1 = 3 and 8 - 6 = 2.

They might not understand that, unlike in addition,

subtraction is not commutative. Or, they might incorrectly multiply 16 x 18 as (10 x 10) + (6 x 8)

because they learned in addition you can add the tens, add the ones, and add the result

as in 16 + 18 --so why not in multiplication? Eventually, they might misinterpret the distributive

property and write 2(3 x 5) as (2 x 3) x (2 x 5). The misconception

might transfer into algebra. For example, they might write 2(ab) = (2a) (2b). Schifter

and Russell illustrated the value of students modeling problems with such examples and then describing their

observations to help overcome misconceptions. They stated:

Deep understanding of arithmetic, central to the K-5 curriculum, rests on three pillars:

- Understanding numbers includes understanding written and oral counting; the structure of the base ten system with whole numbers and decimals; and the meaning of fractions, zero, and quantities less than zero.

- Developing computational fluency includes building a repertoire of accurate, efficient, and flexible strategies for each operation and knowing how and when to apply them.

- Examining the behavior of the operations includes modeling these operations, describing and justifying behaviors that are consequences of those properties, and comparing and contrasting the behaviors of different operations. (Three Pillars section)

Schifter and Russell together with Virginia Bastable are authors of Connecting Arithmetic to Algebra (Professional Book): Strategies for Building Algebraic Thinking in the Elementary Grades (2011).

In Math

Misconceptions, PreK-Grade 5: From Misunderstanding to Deep Understanding

Bamberger, Oberdoff, and Schultz-Ferrell (2010) noted a range of similar

misconceptions that elementary students might bring to the classroom in number

and operations, algebra, geometry, measurement, data analysis and probability.

Students might believe adding fractions is done by adding the numerators and

adding the denominators and not understand the role of a common denominator.

They might believe adding a zero after a number "adds nothing." When comparing decimals less than one,

they might conclude that the decimal with the most digits is

larger. They might believe that you can't compute areas of circles using

"square" units, or that a square is not a rectangle because of its shape.

Fortunately for educators, the authors provide practical strategies and

activities to overcome a range of misconceptions. The key is to

consistently probe their understanding and provide them opportunities to show

and explain their reasoning.

In Math

Misconceptions, PreK-Grade 5: From Misunderstanding to Deep Understanding

Bamberger, Oberdoff, and Schultz-Ferrell (2010) noted a range of similar

misconceptions that elementary students might bring to the classroom in number

and operations, algebra, geometry, measurement, data analysis and probability.

Students might believe adding fractions is done by adding the numerators and

adding the denominators and not understand the role of a common denominator.

They might believe adding a zero after a number "adds nothing." When comparing decimals less than one,

they might conclude that the decimal with the most digits is

larger. They might believe that you can't compute areas of circles using

"square" units, or that a square is not a rectangle because of its shape.

Fortunately for educators, the authors provide practical strategies and

activities to overcome a range of misconceptions. The key is to

consistently probe their understanding and provide them opportunities to show

and explain their reasoning.

Consider misconceptions in the following. Have you ever heard students say (or have you as the teacher said), "To multiply by 10, just add a zero after the number"? Or, "The product of two numbers is always bigger than either one"? How about, "The number with the most digits is the biggest." Without an exploration of place value, students might not fully understand the role of "0" and believe that 9.07 = 9.7 or 5.40 < 5.400. In teaching operations with fractions, students learn when multiplying fractions to multiply the numerators and multiply the denominators as in 2/3 x 4/5 = 8/15. So, they might then incorrectly assume you can do the same when adding or subtracting fractions, as in 2/3 + 4/5 = 6/8. Using manipulatives might help to overcome such fraction misconceptions. Then consider learning about ratios and rates. Students might incorrectly believe "4:4" or "4 to 4" means 1.

Marilyn Burns (2014) suggested the importance of exploring the "why" in mathematics, as misconceptions might be uncovered in doing so. For example, if one is teaching elementary math topics, consider questions like "Why is it OK to add a zero when multiplying whole numbers by 10 but not when multiplying decimals by 10? Why is the sum of two odd numbers always even? Why is zero an even number? Why does canceling zeros produce an equivalent fraction in the fraction 10/20, but not in the fraction 101/201?" Such questions and misconceptions also set the tone for the need to teach mathematics right the first time with a focus on understanding.

In Wayne Snyder's (2013) view, "Without eliciting the mathematical thinking that lies behind the answer, there is no way to tell where understanding breaks down. Only by providing the structure, environment, and opportunity for students to share the reasoning behind their answers can we dislodge misconceptions" (para. 7). Further, reasoning is a cornerstone to understanding:

Eliciting students' thinking is not just about determining their misconceptions; it is also about understanding and encouraging their correct mathematical reasoning. ... Mathematical reasoning is a required part of the new paradigm of mathematics education, underscored and made explicit in the Common Core Standards for Mathematical Practice. Reasoning does not take the place of mathematical processes; rather, it strengthens the understanding, retention, and application of processes. Teaching for mathematical reasoning involves allowing and requiring students to express and to share their reasoning; listening to their explanations; and responding, guiding, and celebrating their mathematical thinking. (para. 9-10)

A focus on understanding is among key instructional shifts for implementing the Common Core State Standards. Certainly, understanding is an element of proficiency and literacy. While procedural skills and fluency are among those shifts with students being expected to have "speed and accuracy in calculation," for deep conceptual understanding, teachers are expected to teach more than how to get the answer and instead support students’ ability "to access concepts from a number of perspectives in order to see math as more than a set of mnemonics or discrete procedures." Further, teachers will need to ensure that students can correctly apply mathematics knowledge in new situations, which "depends on students having a solid conceptual understanding and procedural fluency"(Common Core State Standard Initiative: Shifts in Mathematics, 2010).

This is not to negate the role of memorization in mathematics. Morsund and Ricketts (2010) also noted, "It is well recognized that some rote memory learning is quite important in math education. However, most of this rote learning suffers from a lack of long term retention and from the learner’s inability to transfer this learning to new, challenging problem situations both within the discipline of math and to math-related problem situations outside the discipline of math. Thus, math education (as well as education in other disciplines) has moved in the direction of placing much more emphasis on learning for understanding. There is substantial emphasis on learning some “big ideas” that will last a lifetime" (section 1.1: Math Maturity, para. 1-2).

Barry Garelick (in Hess, 2021) offers a slightly different perspective. Although the "prevailing belief in current math-reform circles is that drilling kills the soul and makes students hate math and that memorizing the facts obscures understanding," he notes "there are some things in math that need to be memorized and drilled, such as addition and multiplication facts. Repetitive practice lies at the heart of mastery of almost every discipline, and mathematics is no exception. No sensible person would suggest eliminating drills from sports, music, or dance. De-emphasize skill and memorization and you take away the child’s primary scaffold for understanding" (para. 2, 3).

Cheryl Rose Tobey and co-authors Carolyn Arline or Emily Fagan have written

four books, each for a grade band, on Uncovering Student Thinking About Mathematics

in the Common Core to

help uncover common math misconceptions related to the Common Core math

standards. Each book is similarly titled. For example, the high school book is

Uncovering Student Thinking About Mathematics in the Common Core, High School: 25 Formative Assessment Probes.

Others are for grades K-2,

3-5, and

6-8. Each book includes diagnostic questions, called formative assessment probes, designed to

help educators to then "systematically address conceptual and procedural

mistakes," identify struggling learners, and better plan for instruction

targeted to mastery of grade level Common Core standards.

Cheryl Rose Tobey and co-authors Carolyn Arline or Emily Fagan have written

four books, each for a grade band, on Uncovering Student Thinking About Mathematics

in the Common Core to

help uncover common math misconceptions related to the Common Core math

standards. Each book is similarly titled. For example, the high school book is

Uncovering Student Thinking About Mathematics in the Common Core, High School: 25 Formative Assessment Probes.

Others are for grades K-2,

3-5, and

6-8. Each book includes diagnostic questions, called formative assessment probes, designed to

help educators to then "systematically address conceptual and procedural

mistakes," identify struggling learners, and better plan for instruction

targeted to mastery of grade level Common Core standards.

Teachers play a significant role in how they plan for instruction and the strategies they use to help learners become mathematically literate and proficient. Per Fuson, Kalchman, and Bransford (in National Research Council, 2005):

"Developing mathematical proficiency requires that students master both the concepts and procedural skills needed to reason and solve problems effectively in a particular domain. Deciding which advanced methods all students should learn to attain proficiency is a policy matter involving judgments about how to use scarce instructional time" (p. 232). Teachers need to maintain a balance "between learner-centered and knowledge-centered needs. The learning path of the class must also continually relate to individual learner knowledge" (p. 235).

A central

strategy for developing mathematical literacy is "enabling

students to find their own independent approaches to learning" (Ulm,

2011, p. 5). Along the way, students will make mistakes and

educators must acknowledge the role that mistakes have for achieving

engagement and learning. In the view of educator Miriam Clifford (2012), "Changing

the way we see errors and the time it takes to learn can help us produce better

learning outcomes" (para. 2). Clifford stated:

A central

strategy for developing mathematical literacy is "enabling

students to find their own independent approaches to learning" (Ulm,

2011, p. 5). Along the way, students will make mistakes and

educators must acknowledge the role that mistakes have for achieving

engagement and learning. In the view of educator Miriam Clifford (2012), "Changing

the way we see errors and the time it takes to learn can help us produce better

learning outcomes" (para. 2). Clifford stated:

According to the Ohio Department of Education (2012), there are multiple ways for developing literacy in the mathematics classroom:

Carpenter, Blanton, Cobb, Franke, Kaput, and McClain (2004) proposed that "there are four related forms of mental activity from which mathematical and scientific understanding emerges: (a) constructing relationships, (b) extending and applying mathematical and scientific knowledge, (c) justifying and explaining generalizations and procedures, and (d) developing a sense of identity related to taking responsibility for making sense of mathematical and scientific knowledge" (pp. 2-3). "Placing students' reasoning at the center of instructional decision making... represents a fundamental challenge to core educational practice" (p. 14).

According to Steve Leinwand and Steve Fleishman (2004), since the 1980s research results "consistently point to the importance of using relational practices for teaching mathematics" (p. 88). Such practices involve explaining, reasoning, and relying on multiple representations that help students develop their own understanding of content. Unfortunately, much instruction begins with instrumental practices involving memorizing and routinely applying procedures and formulas. "In existing research, students who learn rules before they learn concepts tend to score lower than do students who learn concepts first" (p. 88).

Examples:

The importance of addressing misconceptions using relational practices and multiple representations was made clear when a teacher recently voiced concern about being unable to convince a beginning algebra student that (A + B) 2 was not A2 + B2. The following visual helped clarify (A+B) (A+B) = A2 + 2AB +B2

|

A |

B |

|

|

A |

||

|

B |

|

|

This same discussion brought up a comparison to using such a visual for understanding the typical multiplication algorithm in which students have been taught to "leave off the zeroes and move each successive row of digits when multiplying left one place." Students often have no idea as to why they are doing that.

Consider the multiplication problem 31 x 25 and how the distributive property plays a role in the algorithm:

|

20 |

5 |

|

|

30 |

||

|

1 |

The visual suggests that 31 x 25 = (30 + 1)(20 + 5) = (30 x 20) + (30 x 5)+ (1 x 20) + (1 x 5) and that there will be four values (600 + 150 + 20 + 5) to add together after the products are found.

As addition can be done in any order, the above "box method" might make the transition to the traditional vertical presentation of the algorithm easier to understand, as in the following illustration:

|

|

2 |

5 |

|

2 |

5 |

|

|

2 |

5 |

|

|

|

x 3 |

1 |

|

x 3 |

1 |

|

|

x 3 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

0 |

|

2 |

5 |

|

|

2 |

5 |

|

|

1 |

5 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

5 |

0 |

|

7 |

5 |

|

|

|

7 |

7 |

5 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

|

7 |

7 |

5 |

Students at all levels benefit from a visual approach to learning mathematics. Joan Boaler (2016) and colleagues at Stanford University shared the importance of visual mathematics for the brain and learning. They indicated "when students learn through visual approaches, mathematics changes for them, and they are given access to deep and new understandings" (p. 1). Brain research has shown that "When we work on mathematics, in particular, brain activity is spread out across a widely-distributed network, which include two visual pathways: the ventral and dorsal ...Neuroimaging has shown that even when people work on a number calculation, such as 12 x 25, with symbolic digits (12 and 25) our mathematical thinking is grounded in visual processing" (p. 1).

What goes on in the classroom on a daily basis and over the course of a unit of instruction is key to processing information for understanding. Robert Marzano (2009) identified five avenues to understanding: chunking information into small bites, scaffolding, interacting, pacing, and monitoring. Of those, scaffolding is key to the entire process, as it involves the content of those chunks and their presentation in a logical order. After presenting a chunk of reasonable length, it is important for teachers to pause and allow students to interact with each other. A high rate of interaction among learners is a necessary component for understanding. Monitoring enables teachers to determine if a chunk has been understood before moving on. Pacing, how fast or slow to move through chunks, is not easily pre-determined. It depends on being able to read students' understanding and engagement with the content. The Teacher Toolkit includes over 20 tools to check for understanding throughout a lesson, including templates (e.g., 3-2-1, back and forth, buddy journal, entry ticket, exit ticket, four corners, graphic organizers, guided notes, etc.).

In Learning in the Fast Lane: 8 Ways to

Put ALL Students on the Road to Academic Success,

Suzy Rollins (2014) noted an approach to scaffolding divided into two

categories: devices and strategies. Scaffolding devices are concrete

tools such as bookmarks, steps, flowcharts, calculators, cheat sheets,

annotations, memory devices, checklists, organizers, timelines, samples of

completed work. Scaffolding strategies are metacognitive in nature,

such as modeling, think-alouds, reciprocal teaching, and visible thinking

(p. 137). The following illustrate scaffolding devices:

In Learning in the Fast Lane: 8 Ways to

Put ALL Students on the Road to Academic Success,

Suzy Rollins (2014) noted an approach to scaffolding divided into two

categories: devices and strategies. Scaffolding devices are concrete

tools such as bookmarks, steps, flowcharts, calculators, cheat sheets,

annotations, memory devices, checklists, organizers, timelines, samples of

completed work. Scaffolding strategies are metacognitive in nature,

such as modeling, think-alouds, reciprocal teaching, and visible thinking

(p. 137). The following illustrate scaffolding devices:

Within the classroom, how teaching is organized also matters. Spacing out learning over time with review and quizzing helps learners retain information over the course of the school year and beyond. According to research, such spacing and exposure to concepts and facts should occur on at least two occasions, separated by several weeks or months. Students will learn more when teachers alternate their demonstration of a worked problem with a similar problem that students do for practice. This helps students to learn problem solving strategies, enables them to transfer those strategies more easily, and to solve problems faster. Student learning is improved if teachers connect abstract ideas and concrete contexts via stories, simulations, hands-on activities, visual representations, real-world problem solving, and so on. Teachers can also enhance learning by using higher order questioning and providing opportunities for students to develop explanations. This ranges from creating units of study that provoke question-asking and discussion to simply having students explain their thinking after solving a problem (Pashler, Bain, Bottge, et al., 2007).

According

to the National Mathematics Advisory Panel (2008):

According

to the National Mathematics Advisory Panel (2008):

The use of “real-world” contexts to introduce mathematical ideas has been advocated, with the term “real world” being used in varied ways. A synthesis of findings from a small number of high-quality studies indicates that if mathematical ideas are taught using “real-world” contexts, then students’ performance on assessments involving similar “real-world” problems is improved. However, performance on assessments more focused on other aspects of mathematics learning, such as computation, simple word problems, and equation solving, is not improved. (p. xxiii)

Marzano, Pickering, and Pollock (2001) included nine research-based instructional strategies that have a high probability of enhancing student achievement for all students in all subject areas at all grade levels. The authors caution, however, that instructional strategies are only tools and "should not be expected to work equally well in all situations." They are grouped together into three categories for strategies that provide evidence of learning, strategies that help students acquire and integrate learning, and strategies that help students practice, review, and apply learning, as suggested by Pitler, Hubbell, and Kuhn (2012) in Using Technology with Classroom Instruction That Works:

Strategies that provide evidence of learning:

Strategies that provide evidence of learning:

Setting objectives and providing feedback--set a unit goal and help students personalize that goal; use contracts to outline specific goals students should attain and grade they will receive if they meet those goals; use rubrics to help with feedback; provide timely, specific, and corrective feedback; consider letting students lead some feedback sessions.

Reinforcing effort and providing recognition--you might have students keep a weekly log of efforts and achievements with periodic reflections of those. They might even mathematically analyze their data. Find ways to personalize recognition, such as giving individualized awards for accomplishments.

Strategies that help students acquire and integrate learning:

Cues, questions, and advance organizers--these should be highly analytical, should focus on what is important, and are most effective when used before a learning experience.

Nonlinguistic representation--incorporate words and images using symbols to show relationships; use physical models and physical movement to represent information.

Summarizing and note taking--provide guidelines for creating a summary; give time to students to review and revise notes; use a consistent format when note taking.

Cooperative learning--consider common experiences or interests; vary group sizes and objectives. Core components include positive interdependence, group processing, appropriate use of social skills, face-to-face interaction, and individual and group accountability.

Note: Reinforcing effort from the first category also fits into this category to help students.

Strategies that help students practice, review, and apply learning:

Identifying similarities and differences (e.g., comparing, contrasting, classifying, analogies, and metaphors)-- graphic forms, such as Venn diagrams or charts, are useful.

Homework and practice--vary homework by grade level; keep parent involvement to a minimum; provide feedback on all homework; establish a homework policy; be sure students know the purpose of the homework.

Generating and testing hypotheses--a deductive (e.g. predict what might happen if ...) , rather than an inductive, approach works best.

Teaching for Understanding is a project at Harvard University that "helps educators to answer two essential questions: What does it mean to understand something? And what kinds of curricula, learning experiences, and assessment support students in developing understanding?"

Read

Strengthening the Student Toolbox: Study Strategies to Boost Learning

by John Dunlosky (2013, Fall) in American Educator. In

Dunlosky's view, "teaching students how to learn is as important as

teaching them content, because acquiring both the right learning

strategies and background knowledge is important—if not essential—for

promoting lifelong learning" (pp. 12-13). Dunlosky noted the

following summary of the effectiveness of strategies he reviewed and

then provided tips for using effective learning strategies:

Read

Strengthening the Student Toolbox: Study Strategies to Boost Learning

by John Dunlosky (2013, Fall) in American Educator. In

Dunlosky's view, "teaching students how to learn is as important as

teaching them content, because acquiring both the right learning

strategies and background knowledge is important—if not essential—for

promoting lifelong learning" (pp. 12-13). Dunlosky noted the

following summary of the effectiveness of strategies he reviewed and

then provided tips for using effective learning strategies:

Laney Sammons (2011) offers assistance with this endeavor in

Building Mathematical Comprehension: Using Literacy Strategies to Make Meaning. She linked reading comprehension strategies and research to mathematics

instruction. You'll find comprehension strategies for mathematics, strategies

for recognizing and understanding vocabulary, the role of schema theory and

strategies for making math connections, good questioning strategies, the

importance of visualization of mathematical ideas, and how to help learners

enhance their mathematical understanding via inferences and predictions.

There are strategies for teaching learners how to determine mathematical

importance, to synthesize for meaning and for monitoring and repairing

comprehension. Sammons also considers the components of a guided math

classroom. "This resource is aligned to the interdisciplinary themes from the Partnership for

21st Century Skills and supports the Common Core State Standards."

Laney Sammons (2011) offers assistance with this endeavor in

Building Mathematical Comprehension: Using Literacy Strategies to Make Meaning. She linked reading comprehension strategies and research to mathematics

instruction. You'll find comprehension strategies for mathematics, strategies

for recognizing and understanding vocabulary, the role of schema theory and

strategies for making math connections, good questioning strategies, the

importance of visualization of mathematical ideas, and how to help learners

enhance their mathematical understanding via inferences and predictions.

There are strategies for teaching learners how to determine mathematical

importance, to synthesize for meaning and for monitoring and repairing

comprehension. Sammons also considers the components of a guided math

classroom. "This resource is aligned to the interdisciplinary themes from the Partnership for

21st Century Skills and supports the Common Core State Standards."

In

Teaching Students to Communicate Mathematically

Sammons (2018) provided K-8 educators with "strategies for teaching

students to express their mathematical thinking effectively—orally, with

the use of representations, and in writing. Successful literacy

strategies, including word walls, modeling, shared writing and revision,

and exemplars—strategies that show students how to talk about and write

about math" are featured (Ch. 1).

In

Teaching Students to Communicate Mathematically

Sammons (2018) provided K-8 educators with "strategies for teaching

students to express their mathematical thinking effectively—orally, with

the use of representations, and in writing. Successful literacy

strategies, including word walls, modeling, shared writing and revision,

and exemplars—strategies that show students how to talk about and write

about math" are featured (Ch. 1).

Children's Mathematics, Second Edition: Cognitively Guided Instruction

by Thomas Carpenter, Elizabeth Fennema, Megan Franke, Linda Levi, and

Susan Empson (2014) is a go-to source to help children learn mathematics

with understanding. Per its description, highlights include:

Children's Mathematics, Second Edition: Cognitively Guided Instruction

by Thomas Carpenter, Elizabeth Fennema, Megan Franke, Linda Levi, and

Susan Empson (2014) is a go-to source to help children learn mathematics

with understanding. Per its description, highlights include:

Everything that educators do should lead to the achievement of learners. If educators are to teach for deeper learning and put research into practice, then their role also needs to change. Per Martinez, McGrath, and Foster (2016), teachers must:

The process of helping learners develop the ability to transfer knowledge to new problems and situations begins with surface learning, then moves to deep learning, and finally to transfer. John Hattie (2003) noted the following distinction between surface and deep learning:

Surface learning is more about the content (knowing the ideas, and doing what is needed to gain a passing grade), and deep learning more about understanding (relating and extending ideas, and an intention to understand and impose meaning). (p. 9)

Each stage is associated with a variety of strategies. Per Hattie and Donoghue (2016):

If the success criteria is the retention of accurate detail (surface learning) then lower-level learning strategies will be more effective than higher-level strategies. However, if the intention is to help students understand context (deeper learning) with a view to applying it in a new context (transfer), then higher level strategies are also needed. An explicit assumption is that higher level thinking requires a sufficient corpus of lower level surface knowledge to be effective—one cannot move straight to higher level thinking (e.g., problem solving and creative thought) without sufficient level of content knowledge. (Overall messages from the model section)

The National Research Council (2012) provided research-based instructional strategies focusing on deep learning:

According to Douglas Reeves (2006), "Schools that have improved achievement and closed the equity gap engage in holistic accountability, extensive nonfiction writing, frequent common assessments, decisive and immediate interventions, and constructive use of data" (p. 90). Such "accountability includes actions of adults, not merely the scores of students" (p. 83). Among those actions of adults is to assist students with gaining proficiency in a range of their own academic learning skills and behaviors. Writing in relation to the new Common Core State Standards, David Conley (2011) emphasized:

These behaviors include goal setting; study skills, both individually and in groups; self-reflection and the ability to gauge the quality of one's work; persistence with difficult tasks; a belief that effort trumps aptitude; and time-management skills. These behaviors may not be tested directly on common assessments, but without them, students are unlikely to be able to undertake complex learning tasks or take control of their own learning. (p. 20)

Assessments are not just summative, but also formative occurring at least quarterly or more with immediate feedback. Beyond a score, feedback contains detailed item and cluster analysis, and is used to inform future instruction. While individual class teachers might not be able to change student schedules to provide double classes in math or literacy for students in need, they can provide such interventions as homework supervision, break down projects into incremental steps, provide time management strategies, project management strategies, study skills, and help with reading the textbook, all of which are among immediate and decisive intervention strategies. An analysis of data in a constructive manner would reveal effective professional practices and lead to discussion on how they might be replicated (Reeves, 2006).

Educators in all instructional settings who put research into practice should apply "The Seven Principles of Good Practice in Undergraduate Education." Such practice emphasizes "active learning, time management, student-faculty contact, prompt feedback, high expectations, diverse learning styles, and cooperation among students" (Garon, 2000, para. 1). However, to reach an entire class, educators need to create an opportunity for full participation and cooperation among students.

Putting research into practice also involves building a community of learners who understand the significance of mathematics in the real-world, who can dialogue effectively about mathematics, and "do" mathematics. The following sections elaborate further on what educators can do to help achieve that goal:

Embed

Thinking Skills within the Curriculum

Embed

Thinking Skills within the CurriculumIn 1987 Lauren Resnick noted in Education and Learning to Think that "Thinking skills resist the precise forms of definition we have come to associate with the setting of specified objectives for schooling" (p. 2). In spite of a lack of a clear definition, she noted several key features of higher-order thinking that enable one to recognize when it occurs. Higher order thinking:

Visit the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke: Brain Basics: Know Your Brain for an introduction to the brain and how it works.

In Uncommon Sense Teaching: Practical

Insights in Brain Science to Help Students Learn, authors Barbara

Oakley, Beth Rogowsky, and Terrence Sejnowski (2021) delved into building

memory (working memory vs. long-term memory), teaching inclusively (the

importance of working memory capacity), active learning (declarative and

procedural pathways), remedies for procrastination, how human brains evolved

and why this matters for your teaching, building community through habits,

collaborative learning, lesson plans, and more. Rogowsky shared

5 Teaching Tips Using Brain Science (Ofgang, 2023, August) taken from

their book:

In Uncommon Sense Teaching: Practical

Insights in Brain Science to Help Students Learn, authors Barbara

Oakley, Beth Rogowsky, and Terrence Sejnowski (2021) delved into building

memory (working memory vs. long-term memory), teaching inclusively (the

importance of working memory capacity), active learning (declarative and

procedural pathways), remedies for procrastination, how human brains evolved

and why this matters for your teaching, building community through habits,

collaborative learning, lesson plans, and more. Rogowsky shared

5 Teaching Tips Using Brain Science (Ofgang, 2023, August) taken from

their book:

See the table of Thinking and Learning Characteristics of Young People with suggested teaching strategies, presented at PUMUS, the online journal of practical uses of math and science. The table is subdivided into sections for grades K-2, 3-5, and 6-8.

Jay McTighe and Harvey Silver (2020) wrote

Teaching for Deeper Learning: Tools to

Engage Students in Meaning Making. They highlighted the following

seven thinking skills for the classroom that engage learners with active

meaning making leading to deeper and lasting learning:

Jay McTighe and Harvey Silver (2020) wrote

Teaching for Deeper Learning: Tools to

Engage Students in Meaning Making. They highlighted the following

seven thinking skills for the classroom that engage learners with active

meaning making leading to deeper and lasting learning:

Peter Liljedahl

has a 14-point plan for

Building a Thinking Classroom in Math. These are briefly described in his 2017 article at

Edutopia and elaborated upon in his 2021 book

Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grades K-12: 14 Teaching

Practices for Enhancing Learning.

Peter Liljedahl

has a 14-point plan for

Building a Thinking Classroom in Math. These are briefly described in his 2017 article at

Edutopia and elaborated upon in his 2021 book

Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics, Grades K-12: 14 Teaching

Practices for Enhancing Learning.

Liljedahl suggested to begin a math class with a good problem solving "thinking task" rather than direct instruction, form visibly random groups, and use vertical non-permanent surfaces (e.g., whiteboards, blackboards) on which the groups can work to solve the problem. He has some sample problems to give you ideas.

Liljedahl also wrote Modifying Your Thinking Classroom for Different Settings: A Supplement to Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics (2022).

Cautionary Notes:

Although Liljedahl's instructional approach has become quite popular, not everyone agrees with it. Commenting in Don't buy into Building Thinking Classrooms in maths, it's a fad: school leader (Duggan, 2024), author and educator Dr. Greg Ashman stated, "Liljedahl’s instructional approach, designed to get students ‘thinking’, is another dangerous fad that will only misguide teachers and result in years wasted as they work to undo the damage if schools adopt it." Further, "Ashman argues the approach is deeply flawed and runs contrary to explicit teaching – the approach we know works best to build students’ mastery of new concepts." He added, "without strong foundational knowledge stored in long-term memory, novice learners will flounder in the kinds of situations BTC [Building Thinking Classrooms] creates. ... When you’ve got novices, you actually need to teach them things, not just let them get on with trying to solve problems – you actually have to teach them some strategies they can use to solve the problem…" Ashman does acknowledge that Liljedahl has done a lot of research, but "it's not effectiveness research."

Greg Ashman is author of A Little

Guide for Teachers: Cognitive Load Theory (2023).

Greg Ashman is author of A Little

Guide for Teachers: Cognitive Load Theory (2023).

Math teacher Ryan Hooper (2024, April 11) also voiced his disagreement with Liljedahl's approach in The Math Movement Taking Over Our Schools. He noted, "The “Building Thinking Classrooms” approach defies research and common sense." He quoted from a 2006 paper by Kirschner, Sweller, and Clark, which concluded that “there is no body of research supporting the technique” and that, “not only is unguided instruction normally less effective; there is also evidence that it may have negative results when students acquire misconceptions or incomplete or disorganized knowledge.”

The

Foundation for Critical Thinking (2019) proposed the following definition of critical thinking:

The

Foundation for Critical Thinking (2019) proposed the following definition of critical thinking:

"Critical thinking is that mode of thinking — about any subject, content, or problem — in which the thinker improves the quality of his or her thinking by skillfully analyzing, assessing, and reconstructing it. Critical thinking is self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem-solving abilities, as well as a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism."

Teaching critical thinking is domain specific and not an easy task, but there are strategies consistent with research to help learners acquire the ability to think critically. According to Daniel Willingham (2007), a professor of cognitive psychology, "the mental activities that are typically called critical thinking are actually a subset of three types of thinking: reasoning, making judgments and decisions, and problem solving" (p. 11). Studies have revealed that:

"First, critical thinking (as well as scientific thinking and other domain-based thinking) is not a skill. There is not a set of critical thinking skills that can be acquired and deployed regardless of context. Second, there are metacognitive strategies that, once learned, make critical thinking more likely. Third, the ability to think critically (to actually do what the metacognitive strategies call for) depends on domain knowledge and practice." (p. 17)

Willingham (2019) proposed a four-step plan for teaching critical thinking:

In earlier research, Rupert Wegerif (2002) noted, the “emerging consensus, supported by some research evidence, is that the best way to teach thinking skills is not as a separate subject but through ‘infusing’ thinking skills into the teaching of content areas” (p. 3). In agreement, Willingham (2007) added that when learners "don't have much subject matter knowledge, introducing a concept by drawing on student experiences can help" (p. 18). Further, "Learners need to know what the thinking skills are that they are learning and these need to be explicitly modeled, drawn out and re-applied in different contexts. The evidence also suggests that collaborative learning improves the effectiveness of most activities" (Wegerif, 2002, p. 3).

Not only must the strategies be made explicit, but practice is an essential element. Willingham (2007) stated:

The first time (or several times) the concept is introduced, explain it with at least two different examples (possibly examples based on students’ experiences ...), label it so as to identify it as a strategy that can be applied in various contexts, and show how it applies to the course content at hand. In future instances, try naming the appropriate critical thinking strategy to see if students remember it and can figure out how it applies to the material under discussion. With still more practice, students may see which strategy applies without a cue from you. (p. 18)

Research scientists Derek Cabrera and Laura Colosi (Wheeler, 2010) identified yet another approach to teaching thinking skills, the DSRP method, that is tied to four universal patterns that structure knowledge:

DSRP focuses on making teachers and students more metacognitive and can be used in any standards-based curriculum. Cabrera and Colosi believe the system works because it is so simple.

Harvey Silver, Abigail Boutz, and Jay McTighe (2022) proposed five ideas for developing real-world thinking skills, which echo much of the thinking skills noted by Wegerif (2002). They said their IDEAS acronym for complex thinking processes reflects "how expert thinkers analyze and address real-world problems."

The value of the IDEAS acronym lies in its application as a framework for designing "rich [performance] tasks that develop complex, real-world thinking skills across grade levels and content areas" (Silver, Boutz, & McTighe, 2022).

Wegerif (2002) elaborated on each of those:

Information-processing skills: These enable pupils to locate and collect relevant information, to sort, classify, sequence, compare and contrast, and to analyze part/whole relationships.

Reasoning skills: These enable pupils to give reasons for opinions and actions, to draw inferences and make deductions, to use precise language to explain what they think, and to make judgments and decisions informed by reasons or evidence.

Enquiry skills: These enable pupils to ask relevant questions, to pose and define problems, to plan what to do and how to research, to predict outcomes and anticipate consequences, and to test conclusions and improve ideas.

Creative thinking skills: These enable pupils to generate and extend ideas, to suggest hypotheses, to apply imagination, and to look for alternative innovative outcomes.

Evaluation skills: These enable pupils to evaluate information, to judge the value of what they read, hear and do, to develop criteria for judging the value of their own and others’ work or ideas, and to have confidence in their judgments. (pp. 4-5)

Donald Treffinger (2008) distinguished between creative thinking and critical thinking, stating that effective problem solvers need both, as they are actually complementary. The former is used to generate options and the latter to focus thinking. Each form of thinking has associated guidelines and tools, illustrated in the following table.

|

Guidelines and Tools for Creative vs. Critical Thinking |

||

|

Creative |

Critical |

|

| Guidelines | Defer judgment, seek quantity, encourage all possibilities, look for new combinations that might be stronger than any of their parts. | Use affirmative judgment as opposed to being critical, be deliberate--consider the purpose of focusing, consider novelty and not only what has worked in past, stay on course. |

| Tools | Brainstorming | Hits and Hot Spots--selecting promising options and grouping in meaningful ways |

| Force-Fitting--forcing a relationship between two seemingly unrelated ideas | ALoU--acryonym for what to consider when refining and developing options: A - Advantages, L - Limitations, o - ways to overcome limitations, U - Unique features | |

| Attribute Listing | PCA or Paired Comparison Analysis--used to rank options or set priorities | |

| SCAMPER--acronym for how to apply checklist of action words to look for new possibilities: S - Substitute, C - Combine, A - Adapt, M - Magnify or Minify, P - Put to other uses, E - Eliminate, R - Reverse or Rearrange) | Sequence: SML--sequence short, medium, or long-term actions | |

| Morphological Matrix--identify key parameters of task) |

Create Evaluation Matrix-- consider all options and possibilities |

|

| Adapted from Treffinger, D. (2008, Summer). Preparing creative and critical thinkers [online]. Educational Leadership, 65(9). https://www.ascd.org/el/articles/preparing-creative-and-critical-thinkers | ||

John Spencer (2019) discussed the value of adding humor to a classroom, as humor can lead to better creative thinking. "Humor encourages creative risk-taking." It "develops divergent thinking." It "models curiosity and playfulness" and "boosts creative problem-solving." "Creative humor leads to creative fluency."

In consideration of "how expert thinkers analyze and address real-world problems" per Silver, Boutz, and McTighe (2022), there is a movement in teaching computational thinking skills and embedding those in the math curriculum.

A rationale appears to be that computational thinking is used "almost everywhere. In everyday life, at work, in school, across fields as diverse as healthcare, finance, law and music." It's "applicable to everyone" (ComputationalThinking.org).

Per ComputationalThinking.org:

"Computational thinking is a process in which you creatively apply a four-step problem-solving cycle to ideas, challenges and opportunities you encounter to develop and test solutions. The emphasis is learning how to take real-life situations and abstract—often to programs—so a computer can calculate the answer."

As in a spiral, repeat the four steps "in sequence until you reach a solution fit for the original purpose." They include:

- Define questions: Questions should be manageable to tackle. Also "Identify the information you have or will need to obtain in order to solve the problem."

- Abstract to computable form: "Transform the question into an abstract precise form, such as code, diagrams or algorithms ready for computation. Choose the concepts and tools to use to derive a solution."

- Compute answers: "Turn the abstract question into an abstract answer using the power of computation, usually with computers. Identify and resolve operational issues during the computation."

- Interpret results: "Take the abstract answer and interpret the results, recontextualising them in the scope of your original questions and sceptically verifying them. Take another turn to fix or refine."

Actually, readers should be aware that the definitioin of computational thinking has varied from researcher to researcher since the term arose (Cansu & Cansu, 2019). Readers might also conclude that the four steps above are similar to those stated in 1945 by George Polya in his Four Problem-Solving Techniques, which have become a classic for math problem-solving: understand the problem, devise a plan, carry out the plan, and look back. The difference for the computational thinking definition above is in the use of a computer to assist in problem solving.

Skills involved in computational thinking include decomposition, pattern recognition, abstraction, and algorithms. Decomposition involves breaking down a problem into smaller, manageable parts. Pattern recognition, as the name suggests, involves looking for patterns and similarities in problems. Pattern recognition is embedded in the Common Core state standards for mathematical practice in which students "Look for and make use of structure" (CCSS, 2010, MP 7). Abstraction is the process of identifying the important parts of the problem and removing extraneous information. An algorithm is developed with the step-by-step process to solve the problem. Such skills are also advocated in ISTE's Standards for Students (2024), which include that students become computational thinkers, and are reflected in its Operational Definition of Computational Thinking for K-12 Education. ISTE collaborated with the Computer Science Teachers Association on this latter definition.

ComputerBasedMath.org, a long-term project by Conrad Wolfram of Wolfram Research, is promoting computer-based math as a change in how math is taught by "using computers in school as we do in the real world: to replace humans for calculating" (What is CBM? section). You'll find a project repository that includes a collection of problems requiring computational thinking to solve. Projects are designated as beginner, intermediate, and proficient.

To learn more about thinking in the classroom, consider the following:

CueThink is one tool designed "to foster a growth mindset and empower students to see challenges as opportunities." It is presented as "an innovative application and a pedagogy focused on improving critical thinking skills and math collaboration for students in grades 2-12." This tablet and web-based product "captures and presents the thinking process and cognition." Students create a video vignette of their solutions, post to a gallery, and receive feedback from peers and their teacher, thus making math social. George Polya's four-step problem solving method is used: understand, plan, solve, and review.

The Critical Thinking Community comprises The Center for Critical Thinking and Moral Critique and the Foundation For Critical Thinking. "The work of the Foundation is to integrate the Center’s research and theoretical developments, and to create events and resources designed to help educators improve their instruction" (Mission). Resources are numerous at this site, particularly articles that define critical thinking and elaborate on the dimensions of critical thought. Articles are relevant for teaching critical thinking within the mathematics classroom.

In

How to Teach Thinking Skills Within the Common Core, James

Bellanca, Robin Fogarty, and Brian Pete (2012)

identified three essential thinking skills for explicit teaching within

each of seven student proficiencies. Proficiencies and related skills are critical thinking (analyze, evaluate,

problem solve), creative thinking (generate, associate, hypothesize),

complex thinking (clarify, interpret, determine), comprehensive thinking

(understand, infer, compare/contrast), collaborative thinking (explain,

develop, decide), communicative thinking (reason, connect, represent), and

cognitive transfer (synthesize, generalize, apply). Such skills are

explicitly stated within the CCSS or are implicit in the language of the

standards. Each chapter includes an explicit teaching lesson, a

classroom content lesson, a CCSS performance task lesson, and reflection

questions. Online and print resources and reproducibles are also

included.

In

How to Teach Thinking Skills Within the Common Core, James

Bellanca, Robin Fogarty, and Brian Pete (2012)

identified three essential thinking skills for explicit teaching within

each of seven student proficiencies. Proficiencies and related skills are critical thinking (analyze, evaluate,

problem solve), creative thinking (generate, associate, hypothesize),

complex thinking (clarify, interpret, determine), comprehensive thinking

(understand, infer, compare/contrast), collaborative thinking (explain,

develop, decide), communicative thinking (reason, connect, represent), and

cognitive transfer (synthesize, generalize, apply). Such skills are

explicitly stated within the CCSS or are implicit in the language of the

standards. Each chapter includes an explicit teaching lesson, a

classroom content lesson, a CCSS performance task lesson, and reflection

questions. Online and print resources and reproducibles are also

included.

HOT! ISTE's Computational Thinking for All includes teacher resources, a leadership toolkit, and a video on computational thinking called "A digital age skill for everyone." With support from Google, ISTE developed "An Introduction to Computational Thinking for Every Educator," an online course for those who "want to teach students how to systematically solve problems." Also see ISTE's Resource Depository on Exploring Computational Thinking. There are over 140 resources searchable by grade bands (3-5, 6-8, 9-12) and subject, of which there are 94 for mathematics.

Learning.com: Computational Thinking for Students is included within EasyTech K-12 digital literacy curriculum. There are "over 1,000 classroom-ready lessons, activities, interactive games, and videos that help students develop a wide range of technology and computational thinking skills."

HOT!: Visible Thinking, a project at Harvard University, is a "research-based conceptual framework, which aims to integrate the development of students' thinking with content learning across subject matters" (Overview section). Of particular value is the Thinking Routine Toolbox, which "highlights thinking routines developed across a number of research projects at PZ [Harvard University's Project Zero]. A thinking routine is a set of questions or a brief sequence of steps used to scaffold and support student thinking.

Teachers who wish to develop powerful thinkers might also consider the Teaching for Robust Understanding of Mathematics (TRU Math) framework for classroom learning, which Alan Schoenfeld and colleagues at the University of California Berkeley have been developing for several years. It has been successfully applied in classrooms. The framework and supporting documents are posted at the Mathematics Assessment Project. TRU Math focuses on what students do, rather than on what teachers do, and includes five dimensions as seen below: content; cognitive demand; equitable access to content; agency, authority, and identity; and uses of assessment.

Learn more about the skills involved in computational thinking, view the YouTube video: What is Computational Thinking? The skills are explained using everyday examples.

Tech Tip: Computational Thinking is a good resource with examples on how to incorporate computational thinking in math, science, ELA, and social sciences classrooms. This resource is among many for education at The Tech Interactive.

| The Five Dimensions of Powerful Classrooms | |

| Dimension | Attributes |

| Content | The extent to which the content students engage with represents our best current disciplinary understandings (as in CCSS, NGSS, etc.). Students should have opportunities to learn important content and practices, and to develop productive disciplinary habits of mind. |

| Cognitive Demand | The extent to which classroom interactions create and maintain an environment of productive intellectual challenge conducive to students’ disciplinary development. There is a happy medium between spoon-feeding content in bite-sized pieces and having the challenges so large that students are lost at sea. |

| Equitable Access to Content | The extent to which classroom activity structures invite and support the active engagement of all of the students in the classroom with the core content being addressed by the class. No matter how rich the content being discussed, a classroom in which a small number of students get most of the “air time” is not equitable. |

| Agency, Authority, and Identity | The extent to which students have opportunities to “walk the walk and talk the talk,” building on each other’s ideas, in ways that contribute to their development of agency (the capacity and willingness to engage) and authority (recognition for being a good thinker), resulting in positive identities as thinkers and learners. |

| Uses of Assessment | The extent to which the teacher solicits student thinking and subsequent instruction responds to those ideas, by building on productive beginnings or addressing emerging misunderstandings. Powerful instruction “meets students where they are” and gives them opportunities to move forward. |

|

Source: TRU Math

at Mathematics Assessment Project. |

|

Use Tools

and Manipulatives

Use Tools

and Manipulatives"Good mathematics teachers typically use visuals, manipulatives and motion to enhance students’ understanding of mathematical concepts, and the US national organizations for mathematics, such as the National Council for the Teaching of Mathematics (NCTM) and the Mathematical Association of America (MAA) have long advocated for the use of multiple representations in students’ learning of mathematics" (Boaler et al., 2016, p. 1).

Using appropriately tools strategically is among Common Core state standards for mathematical practice. "These tools might include pencil and paper, concrete models, a ruler, a protractor, a calculator, a spreadsheet, a computer algebra system, a statistical package, or dynamic geometry software." Further, proficient students are able to identify math resources such as "digital content located on a website and use them to pose or solve problems. They are able to use technological tools to explore and deepen their understanding of concepts" (CCSS, 2010, Math Practice MP 5).

Students' thinking and understanding will be enhanced by their use of a variety of tools. Adding to the above, include tools for visualization and analysis of mathematics such as graphic organizers, thinking maps, and both concrete and virtual manipulatives. In fact, Overall, Harold Wenglinsky (2004) concluded that "teaching that emphasizes higher-order thinking skills, project based learning, opportunities to solve problems that have multiple solutions, and such hands-on techniques as using manipulatives were all associated with higher performance on the mathematics" National Assessment of Educational Progress among 4th and 8th graders (p. 33). Using such practices to teach for meaning promotes high performance for students at all grade levels.

However, important variables to consider that influence effectiveness of tools and manipulatives (e.g., using graphic organizers) include such things as "grade level, point of implementation, instructional context, and ease of implementation" (Strangman, Vue, Hall, & Meyer, 2003, p. 10). And, there is an important caveat to using manipulatives. As the National Center on Intensive Intervention (2016) reminded educators:

"It is important to note that although students may demonstrate proper use of a manipulative, this does not mean that they understand the concepts behind use of the manipulative. Explicit instruction and student verbalizations, such as explaining the concept or demonstrating use of the manipulative while they verbally describe the mathematical procedure, should accompany all manipulative use." (p. 5)

CT4ME has an entire section devoted to math manipulatives, which includes use of calculators. Here I delve more into graphic organizers and thinking maps.

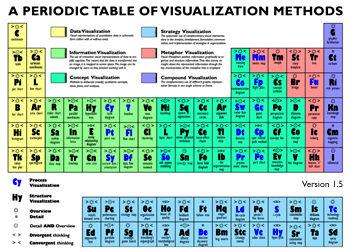

Graphic organizers and thinking maps are just two of the many methods for visualizing and analyzing. Ralph Lengler and Martin Eppler of visual-literacy.org have developed an entire Periodic Table of Visualization Methods from simple to complex.

Within the table (accessed via the link provided above), you can roll

your mouse over each element to learn more about it. You'll find

visualization methods for data, information, concepts, strategies,

metaphors, and compound use of more than one method within the same

scheme. Elements in the table also distinguish between those that

use convergent and divergent thinking, and process and structure

visualization.

Within the table (accessed via the link provided above), you can roll

your mouse over each element to learn more about it. You'll find

visualization methods for data, information, concepts, strategies,

metaphors, and compound use of more than one method within the same

scheme. Elements in the table also distinguish between those that

use convergent and divergent thinking, and process and structure

visualization.

A graphic organizer is defined as "a visual and graphic display that depicts the relationships between facts, terms, and or ideas within a learning task. Graphic organizers are also sometimes referred to as knowledge maps, concept maps, story maps, cognitive organizers, advance organizers, or concept diagrams" (Strangman, Vue, Hall, & Meyer, 2003, p. 2). They are valuable as "a creative alternative to rote memorization"; they "coincide with the brain's style of patterning" and promote this patterning "because material is presented in ways that stimulate students' brains to create meaningful and relevant connections to previously stored memories" (Willis, 2006, Ch. 1, Graphic Organizers section). They are often used in brainstorming and to help learners examine their conceptual understanding of new content.

Graphic organizers might be classified as sequential, relating to a single concept, or multiple concepts. In The Theory Underlying Concept Maps and How to Construct and Use Them, Joseph Novak and Alberto Cañas (2008) stated, concepts within a concept map are "usually enclosed in circles or boxes of some type, and relationships between concepts indicated by a connecting line linking two concepts. Words on the line, referred to as linking words or linking phrases, specify the relationship between the two concepts." Concept is defined as "a perceived regularity in events or objects, or records of events or objects, designated by a label. The label for most concepts is a word, although sometimes we use symbols such as + or %, and sometimes more than one word is used. Propositions are statements about some object or event in the universe, either naturally occurring or constructed. Propositions contain two or more concepts connected using linking words or phrases to form a meaningful statement. Sometimes these are called semantic units, or units of meaning" (Introduction section).

Concept maps are usually developed with in "a hierarchical fashion with the most inclusive, most general concepts at the top of the map and the more specific, less general concepts arranged hierarchically below." Cross-links between sub-domains on the concept map should be added, where possible, as these illustrate that learners understand interrelationships between sub-domains in the map. Specific examples illustrating or clarifying a concept can be added to the concept map, but these would not be placed within ovals or boxes, as they are not concepts (Novak & Cañas, 2008, Introduction section). Novak and Cañas presented examples of concept maps developed with CMap Tools from the Institute for Human and Machine Cognition.

Graphic organizers come in many forms. Other common forms include continuum scales, cycles of events, spider maps, Venn diagrams, compare/contrast matrices, and network tree diagrams. A Venn diagram (two or more overlapping circles) could be used to compare and contrast sets, such as in a study of least common multiple and greatest common factor, or classifying geometric shapes. A tree diagram is useful for determining outcomes in a study of probability of events, permutations and combinations. KWL charts are useful for investigations. Note: CT4ME includes KWL charts in our resource booklets for standardized test prep.

Educators might also wish to expand the KWL chart to a KWHL chart or the ultimate KWHLAQ chart to better promote 21st century skill development. These acronyms represent the following questions:

As an example, students can generate their own graphic organizer using the following sample instructions, adapted from Willis (2006, Ch. 1):

Adapted from J. Willis, Research-based strategies to ignite student learning, (2006, Ch. 1, Graphic Organizers section)

As another example, Metsisto (2005) suggested the Frayer Model and Semantic Feature Analysis Grid. The Frayer Model is used for vocabulary building and is a chart with four quadrants which can hold a definition, some characteristics/facts, examples, and non-examples of the word or concept. The word or concept might be placed at the center of the chart. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction includes a downloadable form for the Frayer Model that students can use.

| Frayer Model | |

| Definition |

Characteristics Facts |

|

Word or Concept |

|

| Examples | Non-Examples |

The Teacher Toolkit includes more on how to use the Frayer Model and downloadable templates.

The Semantic Feature Analysis Grid is a matrix or chart to help students to organize common features and to compare and contrast concepts. Spreadsheets are useful to design these kinds of charts. For example, Metsisto (2005) noted this grid is useful for comparing features of types of quadrilaterals.

Learn more by also reading Knowledge Maps: Tools for Building Structure in Mathematics, in which Astrid Brinkmann (2005) discussed the rules for developing mind maps and concept maps and illustrated how they are used to graphically link ideas and concepts in a well-structured form.

The following are graphic organizer web sites to consider:

Graphic Organizer Maker from Tech4Learning allows you to create custom graphic organizer worksheets for your classroom. There are multiple options from which to choose, including concept maps, KWL, KWHL, timelines, Venn diagrams, flowcharts, cycles, and more.

Graphic Organizers from Education Oasis include multiple types such as cause and effect, compare and contrast, vocabulary development, cycle of events, KWL, and more.

Graphic Organizers from EnchantedLearning.com includes multiple types with explanations of when each is used and printables.

Thinking maps are closely aligned to graphic organizers. Thinking maps are open-ended, allow students to draw on their own experience, and help them to identify, "organize, synthesize, and communicate patterns of information by using a common visual language. They enable students to explore multiple perspectives and to develop metacognitive strategies for planning, monitoring, and reflecting" (Lipton & Hyerle, n.d., p. 6). Lipton and Hyerle also described them, which I have adapted for the following table:

| Thinking Maps | ||

| Type | Purpose | Form |

| Circle | helps students generate and identify information in context related to a topic written inside the inner circle; The map might be enclosed in a square for its frame of reference. |

|

| Tree | can be used both inductively and deductively for classifying or grouping. |

|

| Bubble | can be used for describing the characteristics, qualities or attributes of something with adjectives. Any number of connecting bubbles can extend from the center. |

|

| Double-bubble | useful for comparing and contrasting. |

|

| Flow | enables students to sequence and order events, directions, cycles, and so on. |

|

| Multi-flow | helps to analyze causes and effects of an event |

|

| Brace | useful for identifying part-whole relationships of physical structures. |

|

| Bridge | helps students to interpret analogies and investigate conceptual metaphors |

|

| Adapted from Lipton, L., & Hyerle, D. (n.d.). I see what you mean: Using visual maps to assess student thinking, pp. 2-3. Thinking Foundation. https://www.eggplant.org/tf/research/journal_articles/pdf/lipton-assess-article.pdf | ||

Consider the following resource for thinking guides:

Futurelab Thinking Guides (32 page pdf) "provides a series of ready-made interactive 'thinking guides' or 'frameworks' which can support students' projects and research. Thinking guides support the thinking or working through of an issue, topic or question and help to shape, define and focus an idea and also support the planning required to investigate it further." You'll find guides to map your ideas, analyze, solve problems, explore, investigate different perspectives. You can print, edit, and share the guides with others. You can also make your own and work on them in groups.

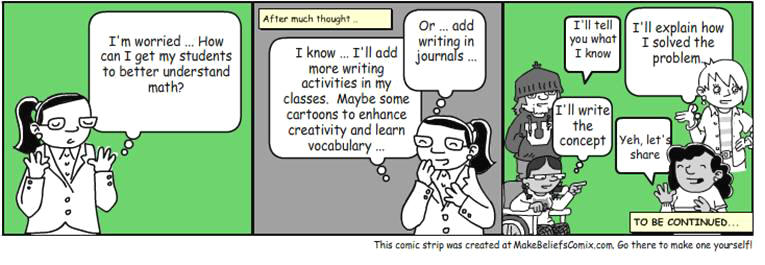

Incorporate Writing and Journaling in Math

Incorporate Writing and Journaling in Math

Problem solving journals and recording problem solving processes create opportunities for students to enhance their metacognition or awareness of what they are doing and why (Rhodes, 2019). As in other curricular areas, writing and journaling in math class helps students to organize and clarify their thoughts and to reflect on their understanding of concepts, or present proofs. A challenge, however, is using math vocabulary appropriately. Reeves (2006) noted, "The most effective writing is nonfiction--description, analysis, and persuasion with evidence" (p. 85). Writing includes "editing, collaborative scoring, constructive teacher feedback, and rewriting" (p. 84) in all subject areas, including math.

Principles

and Standards for School Mathematics (NCTM, 2000) call for students to

communicate about mathematics. Writing across the grades preK-12 is

encouraged and should enable all students to--

Principles

and Standards for School Mathematics (NCTM, 2000) call for students to

communicate about mathematics. Writing across the grades preK-12 is

encouraged and should enable all students to--